When Georgett Watson was in college, she learned that her male best friend was gay. Worried about his safety during the height of the AIDS epidemic, she applied for the position of an administrative assistant at the South Jersey AIDS Alliance. Working her way through nearly all of the positions at the organization, Watson has dedicated most of her life to the cause. 32 years later, she is the CEO of the organization and running Oasis Harm Reduction Center in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

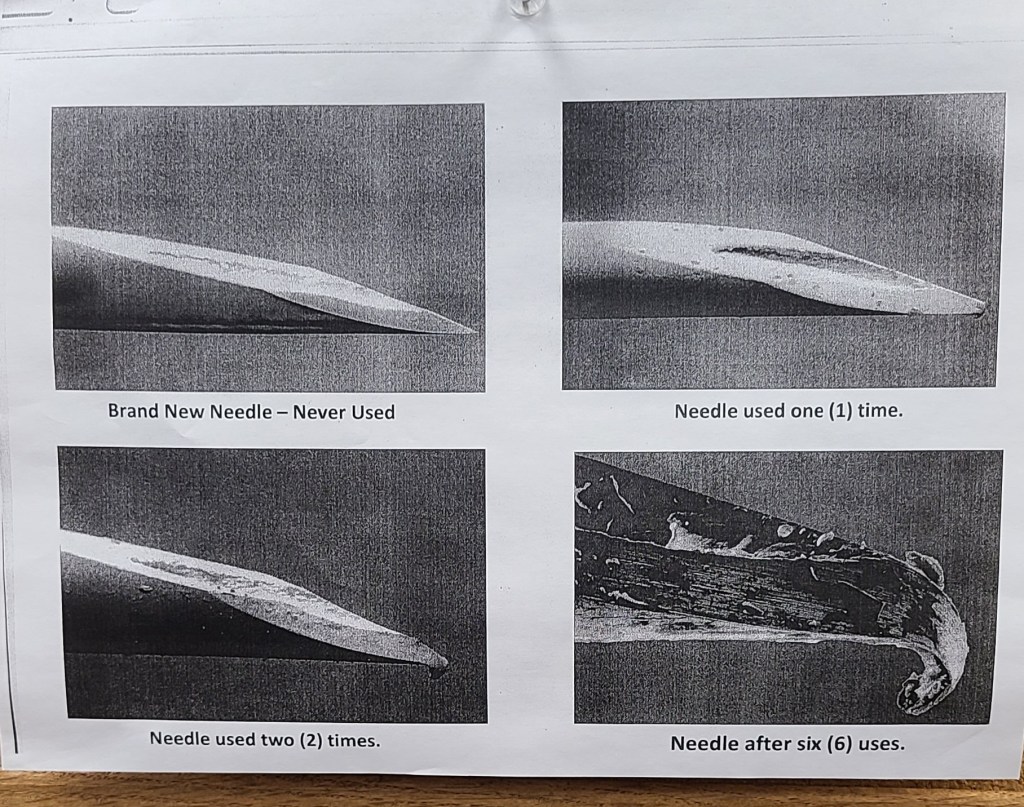

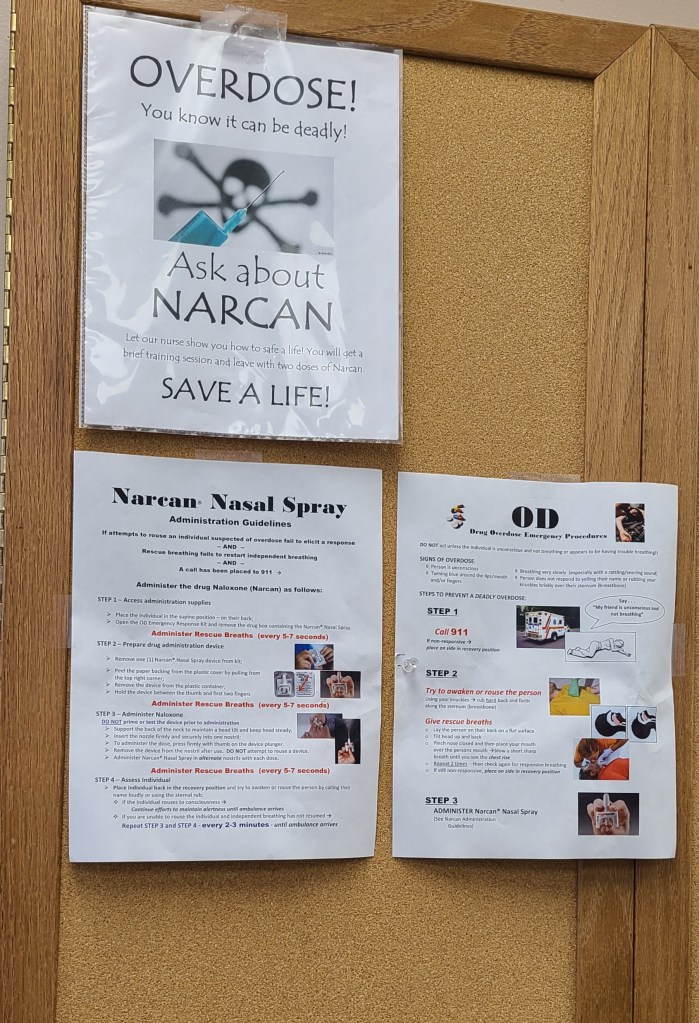

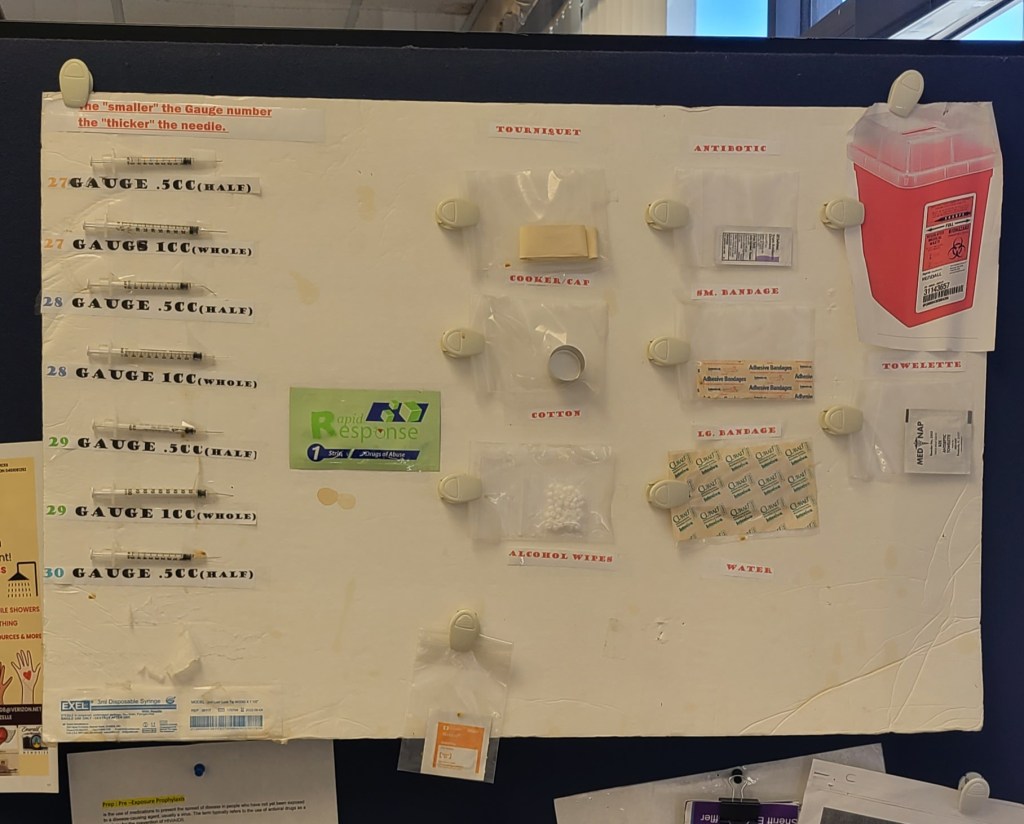

According to the New Jersey Department of Health, Harm Reduction Centers (HRCs) are community-based programs that offer things such as clean syringes, needles, injection equipment, and naloxone (commonly referred to as Narcan) to people who use drugs.

HRCs also serve to educate people on HIV, hepatitis, overdoses, and infectious diseases. At Oasis specifically, they give out socks, blankets, raincoats, and hygiene kits. They also have a shower, washer, and dryer for clients to use. One of the goals of Harm Reduction Centers is to provide a safe, trauma-informed, non-stigmatizing space to the community.

Babette Richter is the lead community health nurse at Oasis and has been there for 13 years. Richter’s job includes working with anyone who is injecting drugs, from teaching them how to shoot drugs safely to avoid abscesses to teaching people and testing them for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Unsatisfied with her prior nursing job, Richter spotted a small ad for the position at Oasis, and not knowing much about what her future job would entail, thought simply, “Why not?”

However, her connection to the cause runs deeper.

“I had a brother who was an injection drug user who died of an overdose…He was a very educated, loving father, businessman, and functional user for years and years and years and years. And then he made a mistake. And now he’s gone,” Richter said.

At Oasis, Watson and Richter stress the importance of making a connection with the patients who come in, as they have found most patients have endured trauma and poor treatment from their emergency room and doctor’s office visits. Sharon McCann, a sociology professor at Rowan University and former social worker, found this same mentality in most of her patients.

McCann worked very closely with addicts in the 1990s before entering the world of academia. One patient who she had worked closely with for years, David, died not because of drugs but because of the negligence of medical workers.

“I was standing next to him in line at a homeless shelter. It was like a one-a-day thing where you had to stand in line to get in there. And he had been complaining for several years about this lump in his throat and none of the doctors really looked at it. It turned out he had an esophageal aneurysm. And while I was standing there, the aneurysm burst and he died right in front of me,” McCann said.

Despite these emotional interactions and connections with addicts, there are mixed views on the concept of harm reduction centers, safe injection sites, and the overall effort to reduce the number of overdoses.

The number of overdoses in Atlantic County has ranged from 171 to 255 since 2019. The New Jersey Department of Law and Public Safety reported that there were 171 overdoses in 2019 in Atlantic County, 201 in 2020, 191 in 2021, 255 in 2022, and 179 suspected drug-related deaths in 2023.

“So you get the NIMBY, the ‘not in my backyard’. People will agree that they like the idea and concept, but they don’t want them anywhere near them. And then there’s the whole group of people who insist that they encourage people to use drugs, which is very similar to the same group of people who insist that if you teach kids about birth control, they’re going to have sex. People are going to do these things either way,” McCann said.

McCann further explained that one of the biggest proponents of people’s negative viewpoints of harm reduction centers may be the ambiguity of the term itself.

“The concept of harm reduction doesn’t mean anything to people. So when things for harm reduction centers were put up initially, the politicians and leaders in the field thought if they use the name harm reduction, kind of vague, don’t know what it is, everybody would be more accepting of them but they weren’t. But when they switched the name to overdose prevention programs, more people were actually willing to have them,” McCann said.

An article from apa.org documents multiple studies that were done that support McCann’s point. For instance, the article references a study conducted by the American Journal of Public Health in 2018 that found that U.S. adults preferred the term “overdose prevention sites” as opposed to “safe consumption sites”. A survey was taken in 2021 by Criminology & Public Policy that produced the same results.

At Oasis, Watson and Richter experience this stigma surrounding their field of work often.

“I was in a meeting recently where somebody was very upset that we may be doing this in their community…We try to say, alright, if you don’t think we need to be here, where can we be? You know there’s this population out there, and we want you to help us find the population so that we can get them what they need…We care about the community, and we want to talk to folks who may be harming themselves– of how to not harm themselves,” Watson said. “What if it was your son or daughter? What if it was your mother or father?”

Leave a comment